In July of 2015, I was living in Delaware with my fiancé. One morning, as he left for work and I began my day of studying for the California bar exam, I felt a twinge of pain in my abdomen. As a 26-year-old woman, I was no stranger to abdominal pain, but this was different and I could feel my face start to cringe. My fiancé noticed the expression, and after a brief moment of mutual concern, I promised to keep an eye on it and we both went about our days.

That was the last time anything felt even vaguely normal in my life.

From there, it was days of misdiagnoses and tests and suggested procedures that threatened my life, followed by an 8-hour surgery that saved it, and a diagnosis that changed it forever. I’ll never forget the feeling and look of that moment; the ineffable pain on my fiancé’s face and my surgeon crying into a gauze pad. It was surreal and awful. Even looking back now, it still doesn’t seem real.

I was diagnosed at stage IV with metastasis to my right ovary and several lymph nodes. I was given eight weeks to recover from my surgery before starting an adjuvant chemotherapy regimen. All I knew about chemo was that it was scary and the only thing that made it less scary was the idea of dealing with it all, married to the man who had stayed by my side. So we moved our wedding date up by a year and got married six weeks later at my parents’ farm. And despite all the heartache and fear of the preceding weeks and the uncertainty on the horizon, I never felt more love so present in any group of people than I did that day. For that, I will always be grateful.

After the wedding passed and chemo began, I started to reckon with the changes cancer had brought to my life. Not only was I dealing with the uncertainty of the potentially abbreviated lifespan—forcing my ideas for a five year plan or even a one-year plan out the window—but also the changes of my day to day were tough to adjust to. The removal of my ovaries forced me into surgical menopause, bringing with it hormonal changes and emotional consequences that were difficult, to say the least. My husband and I moved in with my parents to be closer to my doctors, and began the search for a home, which is stressful under any circumstance. Doctors and

After the wedding passed and chemo began, I started to reckon with the changes cancer had brought to my life. Not only was I dealing with the uncertainty of the potentially abbreviated lifespan—forcing my ideas for a five year plan or even a one-year plan out the window—but also the changes of my day to day were tough to adjust to. The removal of my ovaries forced me into surgical menopause, bringing with it hormonal changes and emotional consequences that were difficult, to say the least. My husband and I moved in with my parents to be closer to my doctors, and began the search for a home, which is stressful under any circumstance. Doctors and  parents dictating what I was to do and residual weakness from my surgery and treatment made me feel whatever autonomy I had achieved as a young person was being ripped away. With my personal and professional goals on permanent hold and a feeling of very little control over the trajectory of my life, I questioned who I even was now that I had cancer.

parents dictating what I was to do and residual weakness from my surgery and treatment made me feel whatever autonomy I had achieved as a young person was being ripped away. With my personal and professional goals on permanent hold and a feeling of very little control over the trajectory of my life, I questioned who I even was now that I had cancer.

I leaned hard on techniques I had developed in dealing with emotional issues of my teen years. I sought professional help in social workers and therapists. I employed cognitive behavioral therapy to gain control over the fear, anxiety, and depression that pervaded my thoughts, and most importantly, I opened up to my friends and family through writing. I shared the unique isolation of being a young adult cancer patient. I shared how much I distrusted my body. I shared when it was uncomfortable and taboo and probably not what anybody wanted to hear. I shared because I needed to be honest. I shared because the more I used my voice, the more I remembered who I was.

In the process, I found that the more I shared my story, the more people shared with me. And through that process, I found common ground with strangers and developed deep bonds with those I already knew.

In the process, I found that the more I shared my story, the more people shared with me. And through that process, I found common ground with strangers and developed deep bonds with those I already knew.

When my treatment was over, I lived briefly in the fantasy that my cancer was gone. And for six months it was. During those six months, I worked two jobs and took the Maryland bar exam, intent on getting my life back on track from this important, but ultimately temporary detour.

All the while, talk of repealing the Affordable Care Act pervaded national consciousness with the upcoming presidential election. Being a law student from 2012 to 2015, I had had the opportunity to understand the implementation and challenges of the law. I was also able to see how  the law had benefited me, with coverage for adult children that extended my father’s insurance plan to cover my life saving surgery at 26 years old. I also had seen how easy it was for me to get a new plan when that one ran out halfway through my chemo. Guaranteed issue meant I didn’t have to worry about being rejected on account of my cancer.

the law had benefited me, with coverage for adult children that extended my father’s insurance plan to cover my life saving surgery at 26 years old. I also had seen how easy it was for me to get a new plan when that one ran out halfway through my chemo. Guaranteed issue meant I didn’t have to worry about being rejected on account of my cancer.

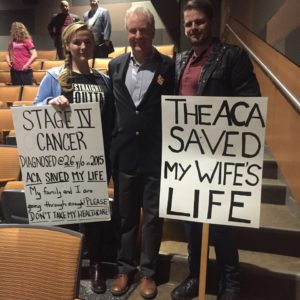

I began to speak out on behalf of the law, to show how it had mitigated a bad situation. I would be lying if I said I didn’t feel a certain responsibility to protect this policy that others had put in place for me. And slowly but surely, my story began to change. Not in facts, but in the way I thought of it. I wasn’t telling the story of the worst thing that ever happened to me: instead I was telling the story of how good policy can make a bad situation just a little bit better.

Again, I found that the more I shared, the more others shared with me, and the more I saw the need to protect patient access to care through whatever policy reform was on the horizon. Slowly but surely, I became part of a network of advocates and activists, ready with a sign or an elevator pitch or speech at a moment’s notice. It was a surprising place to find myself.

Again, I found that the more I shared, the more others shared with me, and the more I saw the need to protect patient access to care through whatever policy reform was on the horizon. Slowly but surely, I became part of a network of advocates and activists, ready with a sign or an elevator pitch or speech at a moment’s notice. It was a surprising place to find myself.

Eventually, the chronic nature of my late-stage disease returned me to the “cancer bubble.” In January of 2017, metastases in my lungs were confirmed with a PET scan and again, the concept of planning for five years or even one was in the wind. My career plans and our alternative family building plans got placed on hold and we lived for a while in surveillance mode, watching the nodules in my lungs grow millimeter by millimeter. The stalling was unbearable.

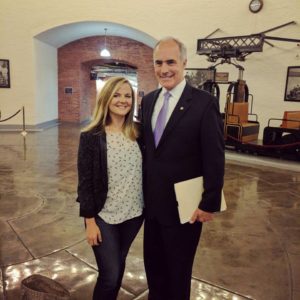

While I was practicing law during this time, I found myself devoting every free moment to advocacy. I found undeniable purpose and community in it. Eventually, after encouragement from family and members of that community, I made the decision to make it my professional purpose, as well as a personal one.

After a short search, I came upon a listing from Fight CRC for a grassroots advocacy manager position. The job involved coordinating advocacy efforts within the colorectal cancer community; communicating with both advocates and legislators about the policy challenges facing colorectal cancer patients. It was also a remote position, which allowed me to be close to and spend my days with my family. It seemed to be written in the stars and it continues to feel that way.

Eventually, treatment was necessitated and I’m now on a clinical trial that involves both chemo and immunotherapy. Working through treatment is tough, but being grounded in professional and personal purpose on a daily basis helps me. And I get to help other patients connect their stories to advocacy and engage in what a friend calls, “policy therapy.” If I can help even one other person find a purpose, or perhaps even a silver lining, to the suffering cancer can bring– well, that’s something.

As a late-stage cancer patient diagnosed very young, it can be easy some days to sink into the anger, jealousy, and pain of it all. But if this experience has taught me anything, it’s that in some things, I do have a choice: I can choose to see the good, to fight for better, and to spend whatever time I have sharing the purpose I’ve found with others. In those choices, there is power. In those choices, I’ve discovered exactly who I am.

LEARN MORE ABOUT COLON CANCER RETURN TO FACES OF BLUE FIGHT CRC

Live and love well! Everyday is a challenge but a positive attitude and smile makes the ugly days dissipate.

See my daughter’s story. Jessica Flanigin West.