They say you’re a survivor from the day you’re diagnosed and while I do consider myself a survivor, I think we are all survivors in our own way. Sometimes I struggle with owning survivorship because of the extreme privilege that I have. The privilege to be alive. Because despite all of the injustices and tragedies of the world, this life I have been given is a gift, and not a gift that I take for granted in the slightest. Sometimes, I feel that the word “survivorship” connotes almost a warrior-like sentiment but that term did not come without a physical and emotional price.

They say you’re a survivor from the day you’re diagnosed and while I do consider myself a survivor, I think we are all survivors in our own way. Sometimes I struggle with owning survivorship because of the extreme privilege that I have. The privilege to be alive. Because despite all of the injustices and tragedies of the world, this life I have been given is a gift, and not a gift that I take for granted in the slightest. Sometimes, I feel that the word “survivorship” connotes almost a warrior-like sentiment but that term did not come without a physical and emotional price.

I don’t see myself as a warrior. I, along with a village of others, was determined to fight against a disease whose odds and statistics were against me. By choice, and with the advice of many healthcare professionals and my former partner’s tenacious support in learning all of my options, I did what I had to do to build a better chance and opportunity to see my children grow up. Knowingly, there is never a guarantee; cancer or no cancer. That was my goal and that was my light at the end of the cancer tunnel. Here lies my trouble with the word: I’m working on acceptance and I am learning how to allow myself a small piece of the survivor pie.

Having cancer has a way of humbling you, it pulls your ego in on the tightest leash and changes your perspective on just about everything possible. It also scares you and makes you question every decision you’ve ever made. I went through a period of time blaming myself for not making healthier lifestyle decisions and then I went through a period of time where I gave myself permission to do whatever the hell I wanted to do because maybe I was going to die. Today, I would say that I am somewhere in the middle. I make healthy choices but I’m not going to be a slave to organic living. There has to be a happy medium.

I remember the day I went to see the colorectal surgeon like it was yesterday. At 31, I had no idea that there were even doctors that specialize in colorectal anything. I was happily nursing my newborn son and wondering if I was ever going to sleep for a consecutive number of hours again. The most traumatic event to my body was surgery on my rotator cuff to fix my non-NCAA throwing arm and then 13 years later, labor and delivery – a 36-hour ordeal. My son Eli was going to come out of me the old fashioned way because that’s how I had it planned in my head. Either way, I didn’t want to have a c-section because I didn’t want to be limited with lifting restrictions for six weeks post-op.

Fast forward to 6-7 months later, here I am at the surgeon’s office. I didn’t prep for a colonoscopy so instead had to get a sigmoidoscopy. Fast forward a couple more years and now the list of surgeries has lengthened. The c-section that I protested because God forbid I should have a scar across my abdomen now seems so nominal. So much for a scar free body, I threw that unrealistic goal out years ago.

My stomach now looks like a tiger because of all of the stretch marks from pregnancy and I now have a scar that goes from my navel to the top of my crotch, three tiny dots tattooed so they could pinpoint radiation, a 6-inch slice in my back with two 2-inch scars on my side and a huge divot in my stomach which my children fondly call my second belly button where a stoma was created for my temporary ostomy bag for the next year of my life.

I remember sitting on the toilet while my then 6-year-old sat on the bathtub across from me trying to explain what I was doing. I told him that my intestines have been rerouted and he looked at me perplexed but curious and without judgement. I remember trying to think of a way he would understand, so I tried my hardest to put it into 5-year-old terms and somehow I came up with this: “You know how the street is closed on the way to Dairy Queen and we have to go a different way to get there?” “Yea momma,” he said. “Well that’s what the doctor did to my intestines where the poop comes from. The poop now has to go down a different street and come out a different way in order to fix the road. My tush is temporarily closed for construction,” I said. Like most children, he didn’t bat an eye at this adversity and then offered up his help.

I remember sitting on the toilet while my then 6-year-old sat on the bathtub across from me trying to explain what I was doing. I told him that my intestines have been rerouted and he looked at me perplexed but curious and without judgement. I remember trying to think of a way he would understand, so I tried my hardest to put it into 5-year-old terms and somehow I came up with this: “You know how the street is closed on the way to Dairy Queen and we have to go a different way to get there?” “Yea momma,” he said. “Well that’s what the doctor did to my intestines where the poop comes from. The poop now has to go down a different street and come out a different way in order to fix the road. My tush is temporarily closed for construction,” I said. Like most children, he didn’t bat an eye at this adversity and then offered up his help.

That wasn’t the only new accessory I got to wear. I was also lucky enough to wear a fanny pack every other week for 48 hours. This fanny pack didn’t carry my chapstick and money, it carried a drug called Fluorouracil or 5-FU. This was connected by an IV line giving me a constant injection into my superior vena cava vein where my power port device was implanted into the top left part of my chest. They implant these for people who need repeated needle sticks to avoid screwing up the veins in your arms. I like to think I had something to do with the fashion statement and resurgence of the fanny pack.

After over a year of treatment, they told me I was in remission and they didn’t have to see me for three months. Three months later I went back after a scan to get the report. This time, the oncologist didn’t call me, so I was confident I was in the clear. I brought my little peanut Eli thinking we were going to get some really good news. He sat on my lap as we listened to the doctor deliver unexpected news instead. The small spots originally thought to be benign histoplasmosis had started growing after ending chemo three months prior. They weren’t picked up in scans before because they were dormant during my aggressive chemo regimen.

I kept it together because that’s what I do. I called my partner Robin and parents. My mother was beside herself and my father  kept his composure. Robin got on the phone to direct traffic because that’s what she’s good at. I wasn’t shy in saying that I was tired of the drugs; tired of the appointments and tired of being tired. Protocol said I didn’t need more chemo if I didn’t want it. My oncologist would respect my opinion to instead let the thoracic surgeon remove a lobe of my lung to go without any more drugs the rest of my life if that’s what I decided. Some of my family demanded that I need to get a second opinion and insisted that I go to the Mayo Clinic. Despite being satisfied with my care in Minneapolis, I went anyway to please them.

kept his composure. Robin got on the phone to direct traffic because that’s what she’s good at. I wasn’t shy in saying that I was tired of the drugs; tired of the appointments and tired of being tired. Protocol said I didn’t need more chemo if I didn’t want it. My oncologist would respect my opinion to instead let the thoracic surgeon remove a lobe of my lung to go without any more drugs the rest of my life if that’s what I decided. Some of my family demanded that I need to get a second opinion and insisted that I go to the Mayo Clinic. Despite being satisfied with my care in Minneapolis, I went anyway to please them.

At the Mayo Clinic, I met a nurse who bluntly asked, “Do you want to live or do you want to die?” I appreciated her forwardness and paused, thinking, “I don’t want any more drugs but I want to live.” She then told me that I needed more chemo. She said to think of it as an insurance policy to wipe out any bad cells that could surface. To have a better chance of seeing my children grow up, I agreed to more treatments. It was another long year, but I was determined not to just become another medical statistic.

I know that I am critical of myself, this is something I want to work on. Friends say that I should honor and respect this time for healing but the universe will not idle while I do my self-help work. A 7 percent survival rate is what they give to people with my kind of cancer when the disease metastasizes and penetrates through the lymphatic tissues and heads towards an organ and invades it. Colorectal cancer is often very treatable and preventable, however, I waited entirely too long to see a doctor and thus the diagnosis progressed. I was young, right? I had no family history and lived a pretty healthy lifestyle. Cancer doesn’t discriminate though. I remember so many people say, “you’re so young.” Yes, I am young. Again, cancer doesn’t discriminate.

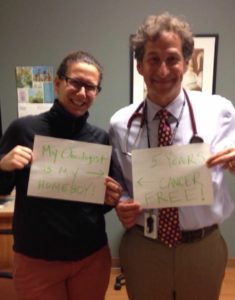

As for the last year, I spend my days substitute teaching, raising two incredible boys (Mason & Eli), and enjoying cancer free life to the fullest all while spreading hope and light wherever I can. As you know, those three words, “you have cancer,” changes our perspective on every aspect of our lives and though there have been other challenges, like losing both of my parents in the same decade of the cancer, I wake in gratitude for everyday I am given.

As for the last year, I spend my days substitute teaching, raising two incredible boys (Mason & Eli), and enjoying cancer free life to the fullest all while spreading hope and light wherever I can. As you know, those three words, “you have cancer,” changes our perspective on every aspect of our lives and though there have been other challenges, like losing both of my parents in the same decade of the cancer, I wake in gratitude for everyday I am given.